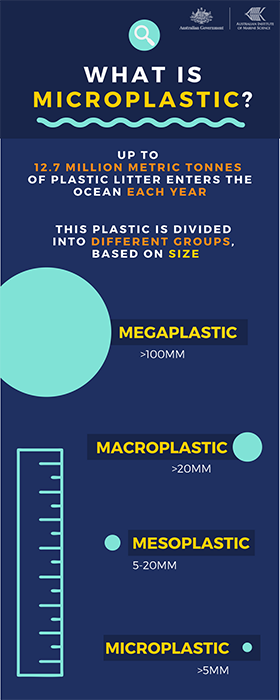

Less than 0.5mm in diameter, billions of tiny particles known as microplastics are having an enormous impact on the world’s oceans and harming marine life up and down the food chain. What can you do about it?

Thanks to plastic bag bans, festivals eliminating single use plastics, and Craig Reucassel’s War on Waste, many of us are more aware of our plastic consumption than we used to be.

UQ has some great programs to support these goals too, including UQ Unwrapped, water refill stations around campus, and campus and office recycling initiatives. Plus, lots of our cafes offer discounts for bringing your own cup.

But despite these efforts, a survey on Australia’s plastic consumption in 2017-18 (the latest federal government figures) showed the nation’s plastic consumption continuing to increase year-on-year. And according to a new international report released by Pew Charitable Trusts in July, our local actions are just the beginning of tackling the global plastics problem.

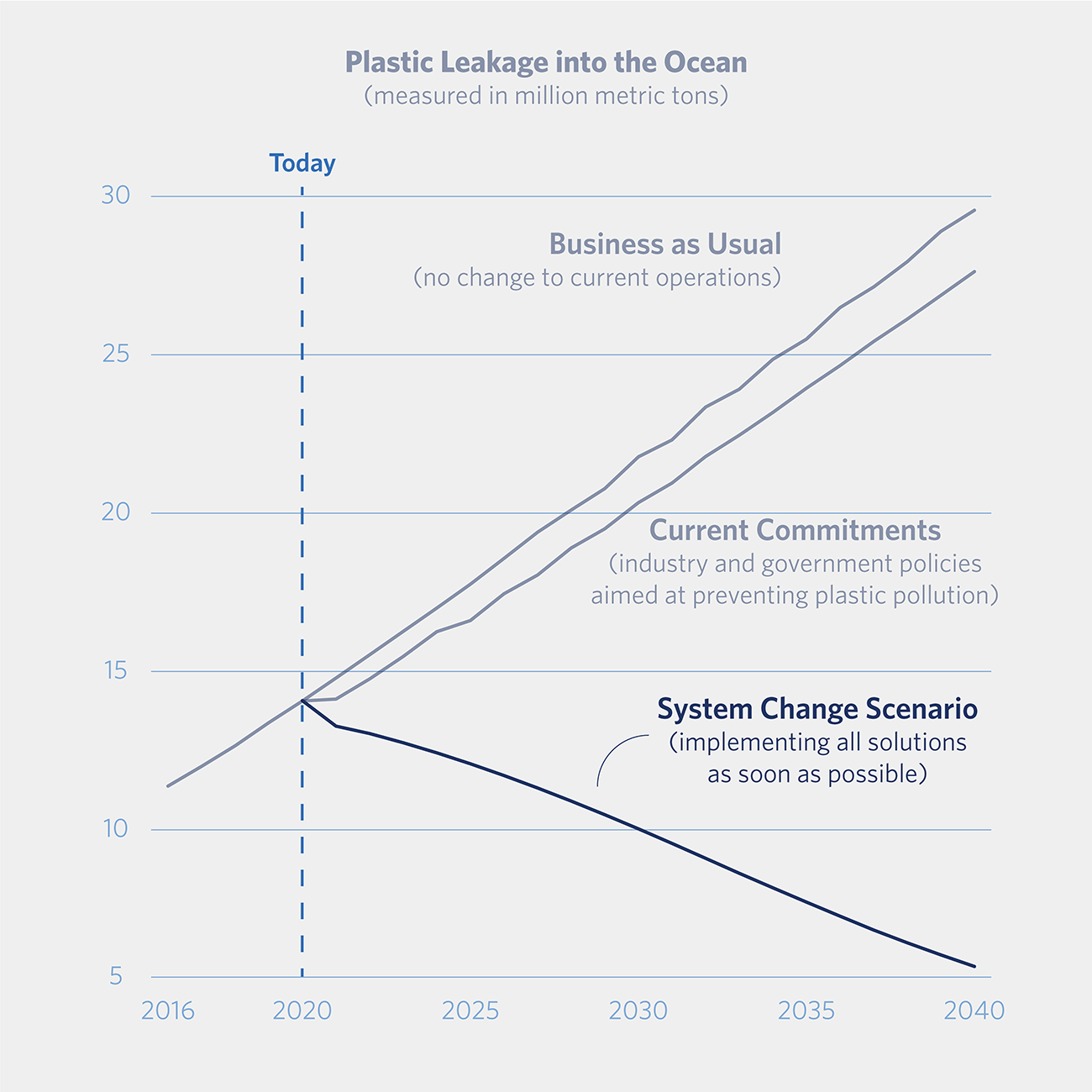

The report predicts the amount of plastic entering our oceans annually will treble by 2040 if the world continues production and consumption at its current rate. It examines plastic waste of all types and sizes to deliver 10 critical findings that, it says, could bring about systemic change and reduce the flow of plastic into our oceans by about 80%.

Acknowledging their significant contribution to the overall problem, the report contains a section dedicated to microplastic interventions. Microplastics are divided into primary sources (those plastics that enter the environment as tiny particles) and secondary sources (larger plastic items that enter the environment and break down over time).

Tyres and pellets are major microplastic sources

If you have heard of microplastics, chances are it’s in connection with the cosmetic industry. Micro beads in exfoliators, as well as even smaller particles in other creams and make-ups, came to the fore a few years back. Many major governments, including notably the US in 2015, have now outlawed microplastics in beauty products.

The Australian Government encouraged industry to undertake a voluntary phaseout of microbeads from cosmetics in 2016. In late 2017, 94% of products on Australian supermarket shelves were assessed as being microbead-free. The government issued a monitoring and assurance protocol in 2018 to support their total removal, but has not yet formally legislated against microbeads.

Conscious consumers can download an app called Beat the Microbead, which allows you to scan the ingredients list of cosmetic products and flags any microplastic-containing elements within.

Tea drinkers may also have been rudely introduced to microplastics when a 2019 study received global coverage after revealing that up to 11.6 billion microplastic particles could leak into a single cup brewed from a plastic tea bag. (Consumers were raising concerns around plastic tea bags for years before that too, but this study was the first to scientifically prove the impacts.)

Yet while the growing consumer attention on microplastics is useful, the Pew report suggests we need to broaden our awareness (see pages 36-37 of the report). Personal care products and textiles combined comprise just 4% of total primary microplastic sources. (If you’re looking for tips regarding clothing, this blog contains a useful list of natural fabrics that don’t release microplastics into the environment.)

Seventy-eight percent of primary microplastic leakage into the ocean comes from tyre abrasion and tyre dust, the report states. A National Geographic article explains that modern tyres typically contain around 19% natural rubber and 24% synthetic rubber, which is a plastic polymer. As we drive, tiny particles constantly break off and are blown or washed into waterways, drains and oceans.

The OECD hosted a workshop this year on microplastics from tyre wear, aiming to address mitigation and policy measures. Results are yet to be published, but solutions remain few and far between. They will likely require a significant redesign of tyres – and possibly roads and surfaces too, to minimise degradation.

For individuals wanting to make a change, the Pew report says that existing tyres show a range of durability and consumers may be able to ask about less abrading types and brands next time they replace their wheels. Reducing driving distances wherever possible is another option, which is, of course, common to many sustainability goals.

The fourth major primary source of microplastic marine pollution (18% by mass) is again one you may not have heard of – nurdles. What are they? As environmental site The Great Nurdle Hunt defines, they are tiny plastic pellets about the size of a lentil, which are used in the production of bigger plastic products. However, throughout the transport and manufacturing process, many of these tiny pellets inevitably make their way into the environment.

Raising consumer awareness of nurdles may help to apply pressure, but solutions here will necessarily be industry-implemented. The Great Nurdle Hunt contains an excellent page of information about nurdle pollution prevention.

The damage done

Most environmental organisations and academics describe microplastics as a relatively ‘new’ area of environmental research. To date, most research on the topic has looked at their impact on oceans and to marine life up and down the food chain.

This National Geographic article, published in August 2020, provides a handy overview of how microplastics spread and the extent to which they are present in oceans—and on land—around the world. New methods are being developed to count marine microplastic particles and, unfortunately, early results reveal previous samples significantly underestimated the quantities.

Another recent article from The Guardian summarises a September 2020 paper from Chinese researchers that analyses the impact of microplastics on soil health. Although this is an even newer area of research, the study shows that microplastic particles leech out from landfill into the earth, as they do at sea. This impacts all sorts of microorganisms like mites, larvae and other tiny creatures who play a vital role in breaking down waste and maintaining soil fertility.

You may also be surprised to learn that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which conjures up images of huge piles of rubbish accumulating in the ocean, is in fact almost entirely made up of microplastics, according to National Geographic. Cleaning this up would be no small challenge, the publication says. For example, a U.S. Government marine debris program has estimated it would take 67 ships one year to clean up less than 1% of the North Pacific Ocean, it quotes.

This is one of the many reasons that solutions in the Pew report focus on eliminating plastic production, as much as trying to recycle its output (more on which, you can read below).

Focusing locally, the Australian Microplastic Assessment Project (AUSMAP) is building an interactive map of microplastic hot spots at locations around the country. You can check out their map so far here.

While fish up and down the food chain consume and are harmed by microplastics, research is inconclusive as to the potential impacts on human health – either from seafood or potentially other types of food consumption. Food Standards Australia New Zealand note they do not consider there to be any immediate consumer health risks, but they do maintain a watching brief on the issue.

The big solutions

The Pew report is thinking big in its approach to plastic. In a top findings summary page, it emphasises that there is no single solution and collaboration will be essential. It highlights that solutions are not one-size-fits-all either, and outlines different priorities for developing and developed nations. It reminds readers that although the greater volume of plastic waste may be coming out of poorer, manufacturing-intensive nations, emissions per capita are far higher in wealthier countries.

In relation to microplastics, it notes that per capita microplastic emissions into oceans from wealthy countries are 3.4 times than in the rest of the world, driven mainly by driving rates, textile washing and overall plastic consumption.

The report identifies 10 critical findings, making recommendations to deliver systemic change over the next 20 years. All of its recommendations apply existing solutions and technology, albeit with substantial capital divestment and reinvestment required.

It demonstrates many areas in which plastic reduction and elimination support diverse United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (to which UQ is equally committed), and shows how proposed changes can help communities and countries improve their economic, health and social outcomes.

As always, we have the opportunity to support these macro changes with our own day-to-day actions. The first step is learning about and understanding the issues. Take the time to read over our microplastics summary and visit some of the links to further information we’ve provided throughout this article. We also have some handy tips for recycling and re-use of plastics in general.

Through our own micro actions, we, too, can make a macro impact.